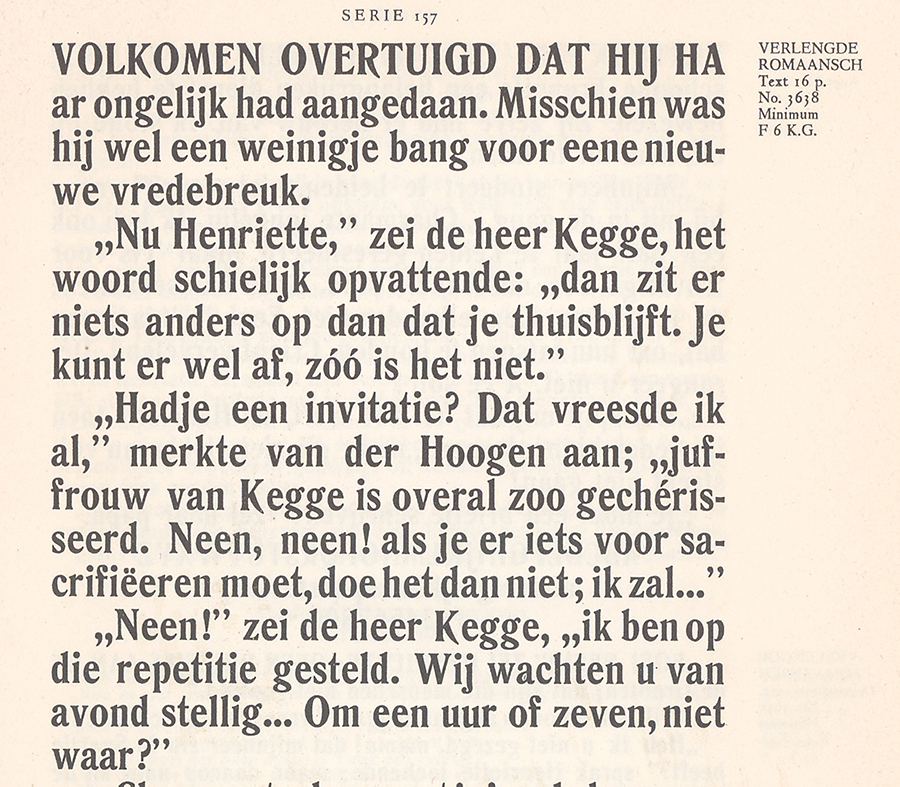

Rodney is an inky revival departing from Enschede Foundry’s 1920s Verlengde Romaansch series. A warm interpretation of fuzzy junctions at smaller sizes became a trait that other design decisions flowed on from.

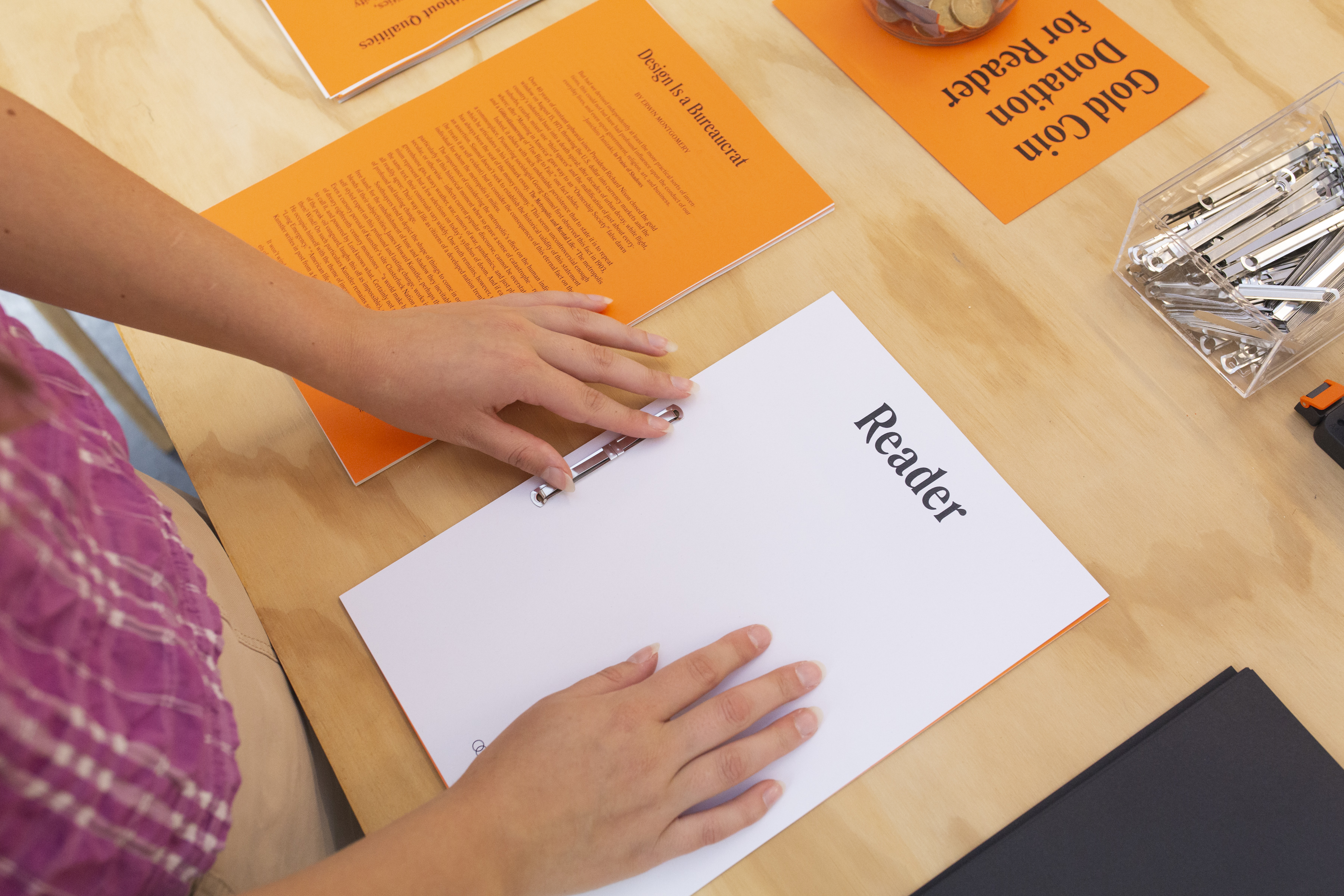

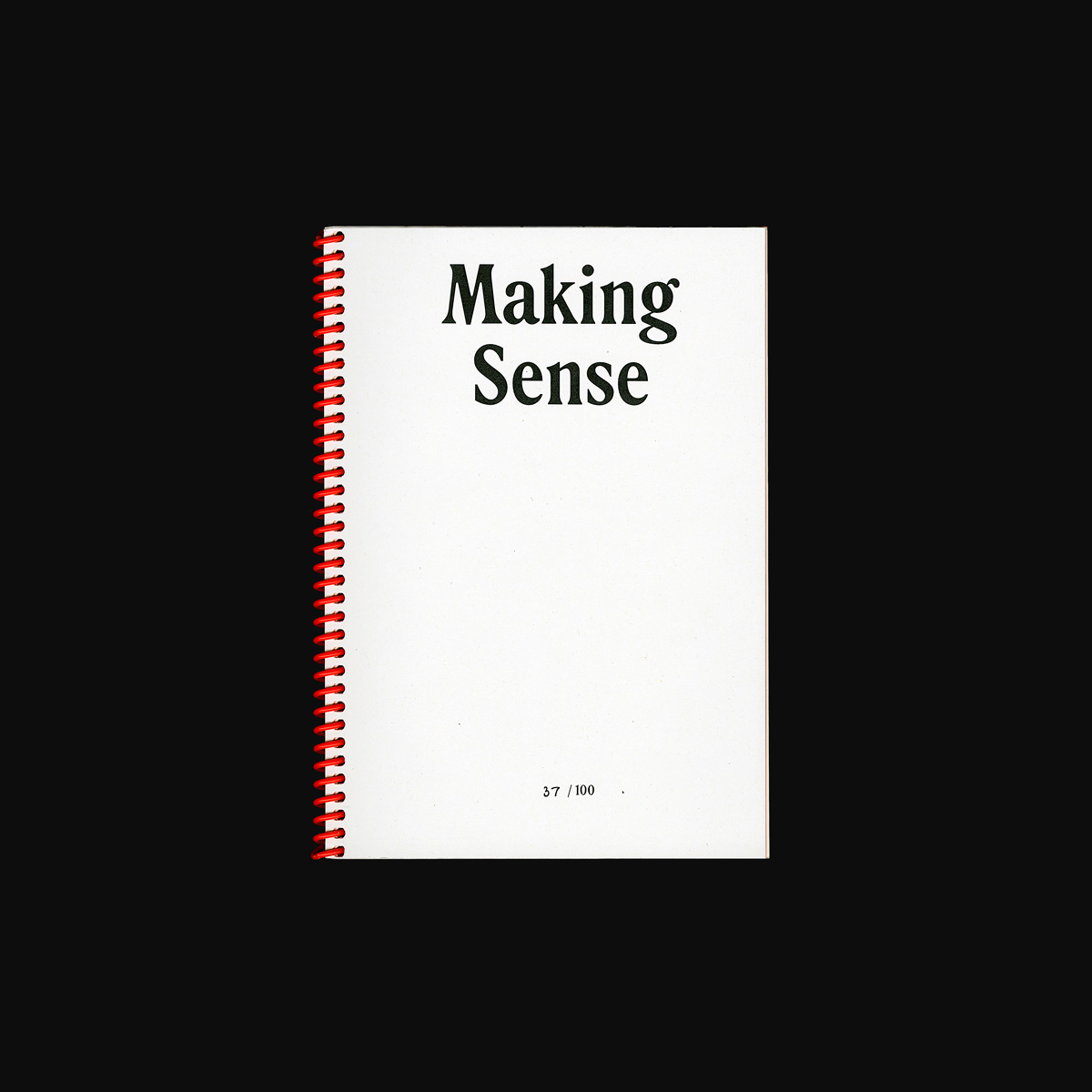

Initial versions of Rodney were drawn for Making Sense, a 2019 exhibition in which the group of designers comprising the collective Making Space sought to raise questions such as: “How can we support, rather than compete?”.

Subsequent years have seen gradual revisions to Rodney — Light and Black weights, a redrawn italic, variable fonts — with recent developments neglecting the original source material in favour of a more self-reflexive and imaginitive approach.

Started: December 2018

Last Update: May 2021

You can download and use this typeface for testing purposes, student work, or explicitly non-commercial, local-scale community organising work. For commercial applications, licenses can be arranged via email.

▤ License Pricing ⤓ Download v2.3Many still consider the State a necessity. Is this so in reality?

Precarity in Design Labour

{xyz}

⚠ DWYL [Do What You Love] is a secreet handshake of the privilaged and a worldview that disguises its elitsim as noble self-betterment —Miya Tokumitsu (2014)

Much the same as with the critical assessment of cartography, the field of graphic design began to question the modernist dogmas that had shaped the field.

2. How can we learn and share knowledge?

Machinery of Government (MOG)

Quota

Consider James Bridle’s A Ship Adrift (2012). Using a website updated on a daily basis, Bridle reconstructs the journey of a navigator adrift.

The Inevitable Rhetorics of Maps

Towards a Machinic Creolization?

$36 @ $2.40ea.

Who is behind the curtain?

Texts

At its root, capitalism is an economic system based on three things: wage labour (working for a wage), private ownership of the means of production (things like factories, machinery, farms, and offices), and production for exchange and profit.

#7031

METADATA

20th Century

$12 Goon Bag

fortissimo

Algorithmic Culture

Dear

abolish monarchy

98%

Machinery of Government (MOG)

abolish monarchy

Who is behind the curtain?

fortissimo

$36 @ $2.40ea.

How can we facilitate critical learning outside of – or in between – tertiary education and commercial practice?

20th Century

Ultimately, only struggle determines outcome, and progress towards a more meaningful community must begin with the will to resist every form of injustice.

At its root, capitalism is an economic system based on three things: wage labour (working for a wage), private ownership of the means of production (things like factories, machinery, farms, and offices), and production for exchange and profit.

Everywhere capitalism developed, peasants and early workers resisted, but were eventually overcome by mass terror and violence.

Choir

Lakes District

Cigar Trade

Texts

Building communities of practice ❤

#7031

the birth of numbers and letters is linked to the emergence of agriculture and sedentarization, notably to inventory harvests and cultivable areas…

Obsequiousness

4, 3, 2, 1

The Inevitable Rhetorics of Maps

Consider James Bridle’s A Ship Adrift (2012). Using a website updated on a daily basis, Bridle reconstructs the journey of a navigator adrift.

Precarity in Design Labour

Towards a Machinic Creolization?

98%

Many still consider the State a necessity. Is this so in reality?

Texts

Both bosses and workers, therefore, are alienated by this process, but in different ways.

Cigar Trade

$12 Goon Bag

George Méliès Cinema, Montreuil

ATALANTA v. INTER MILAN

Obsequiousness

{xyz}

abolish monarchy

Boron & Argon

The Aesthetics of Protest

Lakes District

Our work is the basis of this society. And it is the fact that this society relies on the work we do, while at the same time always squeezing us to maximise profit, that makes it vulnerable.

fortissimo

Algorithmic Culture

98%

Precarity in Design Labour

$42.35

Unionisation and working conditions

METADATA

Towards a Machinic Creolization?

dust clouds

Consider James Bridle’s A Ship Adrift (2012). Using a website updated on a daily basis, Bridle reconstructs the journey of a navigator adrift.

Boron & Argon

(subtext)

The Inevitable Rhetorics of Maps

Texts

$42.35

Quota

Unionisation and working conditions

$12 Goon Bag

fortissimo

Who is behind the curtain?

5. Money for rebuilding the cities. Creation of public works brigades to rebuild inner city areas, made up of community residents.

candlestick

⚠ DWYL [Do What You Love] is a secreet handshake of the privilaged and a worldview that disguises its elitsim as noble self-betterment —Miya Tokumitsu (2014)

❝ How can we support, rather than compete?

George Méliès Cinema, Montreuil

2. How can we learn and share knowledge?

How can we facilitate critical learning outside of – or in between – tertiary education and commercial practice?

Sforzando

Obsequiousness

Both bosses and workers, therefore, are alienated by this process, but in different ways.

Precarity in Design Labour

Towards a Machinic Creolization?

the birth of numbers and letters is linked to the emergence of agriculture and sedentarization, notably to inventory harvests and cultivable areas…

The Aesthetics of Protest

Texts

$42.35

20th Century

(subtext)

Cigar Trade

abolish monarchy

METADATA

Boron & Argon

Unionisation and working conditions

$36 @ $2.40ea.

Capitalism is based on a simple process—money is invested to generate more money.

⚠ DWYL [Do What You Love] is a secreet handshake of the privilaged and a worldview that disguises its elitsim as noble self-betterment —Miya Tokumitsu (2014)

4, 3, 2, 1

Consider James Bridle’s A Ship Adrift (2012). Using a website updated on a daily basis, Bridle reconstructs the journey of a navigator adrift.

Sforzando

#7031

Both bosses and workers, therefore, are alienated by this process, but in different ways.

Ultimately, only struggle determines outcome, and progress towards a more meaningful community must begin with the will to resist every form of injustice.

Our work is the basis of this society. And it is the fact that this society relies on the work we do, while at the same time always squeezing us to maximise profit, that makes it vulnerable.

98%

Building communities of practice ❤

{xyz}

The Aesthetics of Protest

How can we facilitate critical learning outside of – or in between – tertiary education and commercial practice?

2. How can we learn and share knowledge?

#7031

(subtext)

Many still consider the State a necessity. Is this so in reality?

METADATA

Consider James Bridle’s A Ship Adrift (2012). Using a website updated on a daily basis, Bridle reconstructs the journey of a navigator adrift.

❝ How can we support, rather than compete?

Cigar Trade

Quota

dust clouds

$12 Goon Bag

fortissimo

$42.35

The Aesthetics of Protest

4, 3, 2, 1

5. Money for rebuilding the cities. Creation of public works brigades to rebuild inner city areas, made up of community residents.

⚠ DWYL [Do What You Love] is a secreet handshake of the privilaged and a worldview that disguises its elitsim as noble self-betterment —Miya Tokumitsu (2014)

New Urbanism

Texts

98%

Our work is the basis of this society. And it is the fact that this society relies on the work we do, while at the same time always squeezing us to maximise profit, that makes it vulnerable.

Precarity in Design Labour

How can we facilitate critical learning outside of – or in between – tertiary education and commercial practice?

the birth of numbers and letters is linked to the emergence of agriculture and sedentarization, notably to inventory harvests and cultivable areas…

Sforzando

candlestick

Consider James Bridle’s A Ship Adrift (2012). Using a website updated on a daily basis, Bridle reconstructs the journey of a navigator adrift.

The Aesthetics of Protest

$36 @ $2.40ea.

ATALANTA v. INTER MILAN

Dear

George Méliès Cinema, Montreuil

Everywhere capitalism developed, peasants and early workers resisted, but were eventually overcome by mass terror and violence.

DarkSeaGreen #8FBC8F

At its root, capitalism is an economic system based on three things: wage labour (working for a wage), private ownership of the means of production (things like factories, machinery, farms, and offices), and production for exchange and profit.

Algorithmic Culture

abolish monarchy

Building communities of practice ❤

Cigar Trade

4, 3, 2, 1

Unionisation and working conditions

Quota

Towards a Machinic Creolization?

Precarity in Design Labour

the birth of numbers and letters is linked to the emergence of agriculture and sedentarization, notably to inventory harvests and cultivable areas…

(subtext)

How can we facilitate critical learning outside of – or in between – tertiary education and commercial practice?

Lakes District

METADATA

No. 10

fortissimo

Everywhere capitalism developed, peasants and early workers resisted, but were eventually overcome by mass terror and violence.

2. How can we learn and share knowledge?

Ultimately, only struggle determines outcome, and progress towards a more meaningful community must begin with the will to resist every form of injustice.

The Aesthetics of Protest

❝ How can we support, rather than compete?

Both bosses and workers, therefore, are alienated by this process, but in different ways.

Boron & Argon

⚠ DWYL [Do What You Love] is a secreet handshake of the privilaged and a worldview that disguises its elitsim as noble self-betterment —Miya Tokumitsu (2014)

Quota

Machinery of Government (MOG)

George Méliès Cinema, Montreuil

DarkSeaGreen #8FBC8F

4, 3, 2, 1

candlestick

Who is behind the curtain?

#7031

FELLOW WORKERS, WE come before you as Anarchist Communists to explain our principles.

$36 @ $2.40ea.

Choir

20th Century

Cigar Trade

Much the same as with the critical assessment of cartography, the field of graphic design began to question the modernist dogmas that had shaped the field.

Algorithmic Culture

$36 @ $2.40ea.

At its root, capitalism is an economic system based on three things: wage labour (working for a wage), private ownership of the means of production (things like factories, machinery, farms, and offices), and production for exchange and profit.

fortissimo

No. 10

abolish monarchy

The Inevitable Rhetorics of Maps

Unionisation and working conditions

Towards a Machinic Creolization?

98%

Ultimately, only struggle determines outcome, and progress towards a more meaningful community must begin with the will to resist every form of injustice.

Precarity in Design Labour

Both bosses and workers, therefore, are alienated by this process, but in different ways.

Dear

Capitalism is based on a simple process—money is invested to generate more money.

#7031

Machinery of Government (MOG)

The Aesthetics of Protest

$12 Goon Bag

Texts

Choir

Building communities of practice ❤

5. Money for rebuilding the cities. Creation of public works brigades to rebuild inner city areas, made up of community residents.

The Aesthetics of Protest

20th Century

Choir

Cigar Trade

George Méliès Cinema, Montreuil

(subtext)

$12 Goon Bag

$42.35

How can we facilitate critical learning outside of – or in between – tertiary education and commercial practice?

⚠ DWYL [Do What You Love] is a secreet handshake of the privilaged and a worldview that disguises its elitsim as noble self-betterment —Miya Tokumitsu (2014)

Everywhere capitalism developed, peasants and early workers resisted, but were eventually overcome by mass terror and violence.

DarkSeaGreen #8FBC8F

Precarity in Design Labour

METADATA

$36 @ $2.40ea.

abolish monarchy

Machinery of Government (MOG)

Dear

Both bosses and workers, therefore, are alienated by this process, but in different ways.

Sforzando

Algorithmic Culture

Who is behind the curtain?

Building communities of practice ❤

Lakes District

2. How can we learn and share knowledge?

Machinery of Government (MOG)

Precarity in Design Labour

Obsequiousness

$42.35

⚠ DWYL [Do What You Love] is a secreet handshake of the privilaged and a worldview that disguises its elitsim as noble self-betterment —Miya Tokumitsu (2014)

Algorithmic Culture

Choir

Cigar Trade

Many still consider the State a necessity. Is this so in reality?

ATALANTA v. INTER MILAN

At its root, capitalism is an economic system based on three things: wage labour (working for a wage), private ownership of the means of production (things like factories, machinery, farms, and offices), and production for exchange and profit.

20th Century

Dear

(subtext)

George Méliès Cinema, Montreuil

Unionisation and working conditions

dust clouds

abolish monarchy

DarkSeaGreen #8FBC8F

No. 10

Building communities of practice ❤

New Urbanism

candlestick

METADATA

Choir

Quota

Boron & Argon

#7031

Precarity in Design Labour

Texts

5. Money for rebuilding the cities. Creation of public works brigades to rebuild inner city areas, made up of community residents.

Machinery of Government (MOG)

$36 @ $2.40ea.

fortissimo

Unionisation and working conditions

Towards a Machinic Creolization?

Capitalism is based on a simple process—money is invested to generate more money.

$12 Goon Bag

❝ How can we support, rather than compete?

George Méliès Cinema, Montreuil

Cigar Trade

Lakes District

Both bosses and workers, therefore, are alienated by this process, but in different ways.

⚠ DWYL [Do What You Love] is a secreet handshake of the privilaged and a worldview that disguises its elitsim as noble self-betterment —Miya Tokumitsu (2014)

abolish monarchy

{xyz}

ATALANTA v. INTER MILAN

What do I mean by “against students”? By using this expression I am trying to describe a series of speech acts which consistently position students, or at least specific kinds of students, as a threat to education, to free speech, to civilization, even to life itself. In speaking against students, these speech acts also speak for more or less explicitly articulated sets of values: freedom, reason, education, democracy. Students are failing to reproduce the required norms of conduct. Even if that failure is explained as a result of ideological shifts that students are not held responsible for – whether it be neoliberalism, managerialism or a new sexual puritanism – it is in the bodies of students that the failure is located. Students are not transmitting the right message, or are evidence that we have failed to transmit the right message. Students have become an error message, a beep, beep, that is announcing system failure.

In describing the problem of how students have become the problem, I analyze some recent writings that seem to be concerned with distinct issues even if they all address the demise of higher education and involve a kind of nostalgia for something that has been, or is being, lost. I have made the decision to quote from these texts without citing the authors by name. I wish to treat each text as an instance in a wider intertextual web and thus to depersonalise the material. Some of these texts do cite each other, and by evoking the figure of the problem student (who travels through this terrain with an accumulating pace and velocity) they all participate in the making of a shared world.

The “problem student” is a constellation of related figures: the consuming student, the censoring student, the over-sensitive student, and the complaining student. By considering how these figures are related we can explore connections that are being made through them, connections between, for example, neoliberalism in higher education, a concern with safe spaces, and the struggle against sexual harassment. These connections are being made without being explicitly articulated. We need to make these connections explicit in order to challenge them. This is what “against students” is really about.

One of my concerns in Willful Subjects was with the politics of dismissal. I was interested in how various points of view can be dismissed by being swept away or swept up by the charge of willfulness. So: What protesters are protesting about can be ignored when protesters are assumed to be suffering from too much will; they are assumed to be opposing something because they are being oppositional. The figures of the consuming student, censoring student, over-sensitive student, and complaining student are also doing something, they are up to something. These figures circulate in order to sweep something up. Different student protests can be dismissed as products of weaknesses of moral character (generated by “student culture” or “campus politics”) and as the cause of a more general decline in values and standards.

Let’s begin with critiques of neoliberalism and higher education. These are critiques I would share. I too would be critical of how universities are managed as businesses; I too would be critical of the transformation of education into a commodity; of how students are treated as consumers. I too am aware of the burdens of bureaucracy and how we can end up pushing paper around just to leave a trail.

Critiques of neoliberalism can also involve a vigorous sweeping: Whatever is placed near the object of critique becomes the object of critique. For example, my empirical research into the university’s new equality regime taught me how equality can be dismissed as a symptom of neo-liberalism, as “just another” mechanism for ensuring academic compliance. UK Home Secretary and Minister for Women and Equality Theresa May justified a withdrawal from some of the stated commitments in the 2010 Equality Act by arguing the law “would have been just another bureaucratic box to be ticked. It would have meant more time filling in forms and less time focusing on policies that will make a real difference to people’s life chances.” The practitioners I researched in On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life talked of how academics use similar arguments: that these forms and procedures are just another “box to be ticked,” in order to dismiss the more general relevance of equality to their work (“a real difference”). They can then enact non-compliance with equality as a form of resistance to bureaucracy. Equality becomes something imposed by management, as what would, if taken seriously, constrain life and labor. Whilst we might want to critique how equality is bureaucratized, we need to challenge how that very critique can be used to dismiss equality.

What do I mean by “against students”? By using this expression I am trying to describe a series of speech acts which consistently position students, or at least specific kinds of students, as a threat to education, to free speech, to civilization, even to life itself. In speaking against students, these speech acts also speak for more or less explicitly articulated sets of values: freedom, reason, education, democracy. Students are failing to reproduce the required norms of conduct. Even if that failure is explained as a result of ideological shifts that students are not held responsible for – whether it be neoliberalism, managerialism or a new sexual puritanism – it is in the bodies of students that the failure is located. Students are not transmitting the right message, or are evidence that we have failed to transmit the right message. Students have become an error message, a beep, beep, that is announcing system failure.

In describing the problem of how students have become the problem, I analyze some recent writings that seem to be concerned with distinct issues even if they all address the demise of higher education and involve a kind of nostalgia for something that has been, or is being, lost. I have made the decision to quote from these texts without citing the authors by name. I wish to treat each text as an instance in a wider intertextual web and thus to depersonalise the material. Some of these texts do cite each other, and by evoking the figure of the problem student (who travels through this terrain with an accumulating pace and velocity) they all participate in the making of a shared world.

The “problem student” is a constellation of related figures: the consuming student, the censoring student, the over-sensitive student, and the complaining student. By considering how these figures are related we can explore connections that are being made through them, connections between, for example, neoliberalism in higher education, a concern with safe spaces, and the struggle against sexual harassment. These connections are being made without being explicitly articulated. We need to make these connections explicit in order to challenge them. This is what “against students” is really about.

One of my concerns in Willful Subjects was with the politics of dismissal. I was interested in how various points of view can be dismissed by being swept away or swept up by the charge of willfulness. So: What protesters are protesting about can be ignored when protesters are assumed to be suffering from too much will; they are assumed to be opposing something because they are being oppositional. The figures of the consuming student, censoring student, over-sensitive student, and complaining student are also doing something, they are up to something. These figures circulate in order to sweep something up. Different student protests can be dismissed as products of weaknesses of moral character (generated by “student culture” or “campus politics”) and as the cause of a more general decline in values and standards.

Let’s begin with critiques of neoliberalism and higher education. These are critiques I would share. I too would be critical of how universities are managed as businesses; I too would be critical of the transformation of education into a commodity; of how students are treated as consumers. I too am aware of the burdens of bureaucracy and how we can end up pushing paper around just to leave a trail.

Critiques of neoliberalism can also involve a vigorous sweeping: Whatever is placed near the object of critique becomes the object of critique. For example, my empirical research into the university’s new equality regime taught me how equality can be dismissed as a symptom of neo-liberalism, as “just another” mechanism for ensuring academic compliance. UK Home Secretary and Minister for Women and Equality Theresa May justified a withdrawal from some of the stated commitments in the 2010 Equality Act by arguing the law “would have been just another bureaucratic box to be ticked. It would have meant more time filling in forms and less time focusing on policies that will make a real difference to people’s life chances.” The practitioners I researched in On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life talked of how academics use similar arguments: that these forms and procedures are just another “box to be ticked,” in order to dismiss the more general relevance of equality to their work (“a real difference”). They can then enact non-compliance with equality as a form of resistance to bureaucracy. Equality becomes something imposed by management, as what would, if taken seriously, constrain life and labor. Whilst we might want to critique how equality is bureaucratized, we need to challenge how that very critique can be used to dismiss equality.

What do I mean by “against students”? By using this expression I am trying to describe a series of speech acts which consistently position students, or at least specific kinds of students, as a threat to education, to free speech, to civilization, even to life itself. In speaking against students, these speech acts also speak for more or less explicitly articulated sets of values: freedom, reason, education, democracy. Students are failing to reproduce the required norms of conduct. Even if that failure is explained as a result of ideological shifts that students are not held responsible for – whether it be neoliberalism, managerialism or a new sexual puritanism – it is in the bodies of students that the failure is located. Students are not transmitting the right message, or are evidence that we have failed to transmit the right message. Students have become an error message, a beep, beep, that is announcing system failure.

In describing the problem of how students have become the problem, I analyze some recent writings that seem to be concerned with distinct issues even if they all address the demise of higher education and involve a kind of nostalgia for something that has been, or is being, lost. I have made the decision to quote from these texts without citing the authors by name. I wish to treat each text as an instance in a wider intertextual web and thus to depersonalise the material. Some of these texts do cite each other, and by evoking the figure of the problem student (who travels through this terrain with an accumulating pace and velocity) they all participate in the making of a shared world.

The “problem student” is a constellation of related figures: the consuming student, the censoring student, the over-sensitive student, and the complaining student. By considering how these figures are related we can explore connections that are being made through them, connections between, for example, neoliberalism in higher education, a concern with safe spaces, and the struggle against sexual harassment. These connections are being made without being explicitly articulated. We need to make these connections explicit in order to challenge them. This is what “against students” is really about.

One of my concerns in Willful Subjects was with the politics of dismissal. I was interested in how various points of view can be dismissed by being swept away or swept up by the charge of willfulness. So: What protesters are protesting about can be ignored when protesters are assumed to be suffering from too much will; they are assumed to be opposing something because they are being oppositional. The figures of the consuming student, censoring student, over-sensitive student, and complaining student are also doing something, they are up to something. These figures circulate in order to sweep something up. Different student protests can be dismissed as products of weaknesses of moral character (generated by “student culture” or “campus politics”) and as the cause of a more general decline in values and standards.

Let’s begin with critiques of neoliberalism and higher education. These are critiques I would share. I too would be critical of how universities are managed as businesses; I too would be critical of the transformation of education into a commodity; of how students are treated as consumers. I too am aware of the burdens of bureaucracy and how we can end up pushing paper around just to leave a trail.

Critiques of neoliberalism can also involve a vigorous sweeping: Whatever is placed near the object of critique becomes the object of critique. For example, my empirical research into the university’s new equality regime taught me how equality can be dismissed as a symptom of neo-liberalism, as “just another” mechanism for ensuring academic compliance. UK Home Secretary and Minister for Women and Equality Theresa May justified a withdrawal from some of the stated commitments in the 2010 Equality Act by arguing the law “would have been just another bureaucratic box to be ticked. It would have meant more time filling in forms and less time focusing on policies that will make a real difference to people’s life chances.” The practitioners I researched in On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life talked of how academics use similar arguments: that these forms and procedures are just another “box to be ticked,” in order to dismiss the more general relevance of equality to their work (“a real difference”). They can then enact non-compliance with equality as a form of resistance to bureaucracy. Equality becomes something imposed by management, as what would, if taken seriously, constrain life and labor. Whilst we might want to critique how equality is bureaucratized, we need to challenge how that very critique can be used to dismiss equality.

What do I mean by “against students”? By using this expression I am trying to describe a series of speech acts which consistently position students, or at least specific kinds of students, as a threat to education, to free speech, to civilization, even to life itself. In speaking against students, these speech acts also speak for more or less explicitly articulated sets of values: freedom, reason, education, democracy. Students are failing to reproduce the required norms of conduct. Even if that failure is explained as a result of ideological shifts that students are not held responsible for – whether it be neoliberalism, managerialism or a new sexual puritanism – it is in the bodies of students that the failure is located. Students are not transmitting the right message, or are evidence that we have failed to transmit the right message. Students have become an error message, a beep, beep, that is announcing system failure.

In describing the problem of how students have become the problem, I analyze some recent writings that seem to be concerned with distinct issues even if they all address the demise of higher education and involve a kind of nostalgia for something that has been, or is being, lost. I have made the decision to quote from these texts without citing the authors by name. I wish to treat each text as an instance in a wider intertextual web and thus to depersonalise the material. Some of these texts do cite each other, and by evoking the figure of the problem student (who travels through this terrain with an accumulating pace and velocity) they all participate in the making of a shared world.

The “problem student” is a constellation of related figures: the consuming student, the censoring student, the over-sensitive student, and the complaining student. By considering how these figures are related we can explore connections that are being made through them, connections between, for example, neoliberalism in higher education, a concern with safe spaces, and the struggle against sexual harassment. These connections are being made without being explicitly articulated. We need to make these connections explicit in order to challenge them. This is what “against students” is really about.

One of my concerns in Willful Subjects was with the politics of dismissal. I was interested in how various points of view can be dismissed by being swept away or swept up by the charge of willfulness. So: What protesters are protesting about can be ignored when protesters are assumed to be suffering from too much will; they are assumed to be opposing something because they are being oppositional. The figures of the consuming student, censoring student, over-sensitive student, and complaining student are also doing something, they are up to something. These figures circulate in order to sweep something up. Different student protests can be dismissed as products of weaknesses of moral character (generated by “student culture” or “campus politics”) and as the cause of a more general decline in values and standards.

Let’s begin with critiques of neoliberalism and higher education. These are critiques I would share. I too would be critical of how universities are managed as businesses; I too would be critical of the transformation of education into a commodity; of how students are treated as consumers. I too am aware of the burdens of bureaucracy and how we can end up pushing paper around just to leave a trail.

Critiques of neoliberalism can also involve a vigorous sweeping: Whatever is placed near the object of critique becomes the object of critique. For example, my empirical research into the university’s new equality regime taught me how equality can be dismissed as a symptom of neo-liberalism, as “just another” mechanism for ensuring academic compliance. UK Home Secretary and Minister for Women and Equality Theresa May justified a withdrawal from some of the stated commitments in the 2010 Equality Act by arguing the law “would have been just another bureaucratic box to be ticked. It would have meant more time filling in forms and less time focusing on policies that will make a real difference to people’s life chances.” The practitioners I researched in On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life talked of how academics use similar arguments: that these forms and procedures are just another “box to be ticked,” in order to dismiss the more general relevance of equality to their work (“a real difference”). They can then enact non-compliance with equality as a form of resistance to bureaucracy. Equality becomes something imposed by management, as what would, if taken seriously, constrain life and labor. Whilst we might want to critique how equality is bureaucratized, we need to challenge how that very critique can be used to dismiss equality.

What do I mean by “against students”? By using this expression I am trying to describe a series of speech acts which consistently position students, or at least specific kinds of students, as a threat to education, to free speech, to civilization, even to life itself. In speaking against students, these speech acts also speak for more or less explicitly articulated sets of values: freedom, reason, education, democracy. Students are failing to reproduce the required norms of conduct. Even if that failure is explained as a result of ideological shifts that students are not held responsible for – whether it be neoliberalism, managerialism or a new sexual puritanism – it is in the bodies of students that the failure is located. Students are not transmitting the right message, or are evidence that we have failed to transmit the right message. Students have become an error message, a beep, beep, that is announcing system failure.

In describing the problem of how students have become the problem, I analyze some recent writings that seem to be concerned with distinct issues even if they all address the demise of higher education and involve a kind of nostalgia for something that has been, or is being, lost. I have made the decision to quote from these texts without citing the authors by name. I wish to treat each text as an instance in a wider intertextual web and thus to depersonalise the material. Some of these texts do cite each other, and by evoking the figure of the problem student (who travels through this terrain with an accumulating pace and velocity) they all participate in the making of a shared world.

The “problem student” is a constellation of related figures: the consuming student, the censoring student, the over-sensitive student, and the complaining student. By considering how these figures are related we can explore connections that are being made through them, connections between, for example, neoliberalism in higher education, a concern with safe spaces, and the struggle against sexual harassment. These connections are being made without being explicitly articulated. We need to make these connections explicit in order to challenge them. This is what “against students” is really about.

One of my concerns in Willful Subjects was with the politics of dismissal. I was interested in how various points of view can be dismissed by being swept away or swept up by the charge of willfulness. So: What protesters are protesting about can be ignored when protesters are assumed to be suffering from too much will; they are assumed to be opposing something because they are being oppositional. The figures of the consuming student, censoring student, over-sensitive student, and complaining student are also doing something, they are up to something. These figures circulate in order to sweep something up. Different student protests can be dismissed as products of weaknesses of moral character (generated by “student culture” or “campus politics”) and as the cause of a more general decline in values and standards.

Let’s begin with critiques of neoliberalism and higher education. These are critiques I would share. I too would be critical of how universities are managed as businesses; I too would be critical of the transformation of education into a commodity; of how students are treated as consumers. I too am aware of the burdens of bureaucracy and how we can end up pushing paper around just to leave a trail.

Critiques of neoliberalism can also involve a vigorous sweeping: Whatever is placed near the object of critique becomes the object of critique. For example, my empirical research into the university’s new equality regime taught me how equality can be dismissed as a symptom of neo-liberalism, as “just another” mechanism for ensuring academic compliance. UK Home Secretary and Minister for Women and Equality Theresa May justified a withdrawal from some of the stated commitments in the 2010 Equality Act by arguing the law “would have been just another bureaucratic box to be ticked. It would have meant more time filling in forms and less time focusing on policies that will make a real difference to people’s life chances.” The practitioners I researched in On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life talked of how academics use similar arguments: that these forms and procedures are just another “box to be ticked,” in order to dismiss the more general relevance of equality to their work (“a real difference”). They can then enact non-compliance with equality as a form of resistance to bureaucracy. Equality becomes something imposed by management, as what would, if taken seriously, constrain life and labor. Whilst we might want to critique how equality is bureaucratized, we need to challenge how that very critique can be used to dismiss equality.

What do I mean by “against students”? By using this expression I am trying to describe a series of speech acts which consistently position students, or at least specific kinds of students, as a threat to education, to free speech, to civilization, even to life itself. In speaking against students, these speech acts also speak for more or less explicitly articulated sets of values: freedom, reason, education, democracy. Students are failing to reproduce the required norms of conduct. Even if that failure is explained as a result of ideological shifts that students are not held responsible for – whether it be neoliberalism, managerialism or a new sexual puritanism – it is in the bodies of students that the failure is located. Students are not transmitting the right message, or are evidence that we have failed to transmit the right message. Students have become an error message, a beep, beep, that is announcing system failure.

In describing the problem of how students have become the problem, I analyze some recent writings that seem to be concerned with distinct issues even if they all address the demise of higher education and involve a kind of nostalgia for something that has been, or is being, lost. I have made the decision to quote from these texts without citing the authors by name. I wish to treat each text as an instance in a wider intertextual web and thus to depersonalise the material. Some of these texts do cite each other, and by evoking the figure of the problem student (who travels through this terrain with an accumulating pace and velocity) they all participate in the making of a shared world.

The “problem student” is a constellation of related figures: the consuming student, the censoring student, the over-sensitive student, and the complaining student. By considering how these figures are related we can explore connections that are being made through them, connections between, for example, neoliberalism in higher education, a concern with safe spaces, and the struggle against sexual harassment. These connections are being made without being explicitly articulated. We need to make these connections explicit in order to challenge them. This is what “against students” is really about.

One of my concerns in Willful Subjects was with the politics of dismissal. I was interested in how various points of view can be dismissed by being swept away or swept up by the charge of willfulness. So: What protesters are protesting about can be ignored when protesters are assumed to be suffering from too much will; they are assumed to be opposing something because they are being oppositional. The figures of the consuming student, censoring student, over-sensitive student, and complaining student are also doing something, they are up to something. These figures circulate in order to sweep something up. Different student protests can be dismissed as products of weaknesses of moral character (generated by “student culture” or “campus politics”) and as the cause of a more general decline in values and standards.

Let’s begin with critiques of neoliberalism and higher education. These are critiques I would share. I too would be critical of how universities are managed as businesses; I too would be critical of the transformation of education into a commodity; of how students are treated as consumers. I too am aware of the burdens of bureaucracy and how we can end up pushing paper around just to leave a trail.

Critiques of neoliberalism can also involve a vigorous sweeping: Whatever is placed near the object of critique becomes the object of critique. For example, my empirical research into the university’s new equality regime taught me how equality can be dismissed as a symptom of neo-liberalism, as “just another” mechanism for ensuring academic compliance. UK Home Secretary and Minister for Women and Equality Theresa May justified a withdrawal from some of the stated commitments in the 2010 Equality Act by arguing the law “would have been just another bureaucratic box to be ticked. It would have meant more time filling in forms and less time focusing on policies that will make a real difference to people’s life chances.” The practitioners I researched in On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life talked of how academics use similar arguments: that these forms and procedures are just another “box to be ticked,” in order to dismiss the more general relevance of equality to their work (“a real difference”). They can then enact non-compliance with equality as a form of resistance to bureaucracy. Equality becomes something imposed by management, as what would, if taken seriously, constrain life and labor. Whilst we might want to critique how equality is bureaucratized, we need to challenge how that very critique can be used to dismiss equality.

What do I mean by “against students”? By using this expression I am trying to describe a series of speech acts which consistently position students, or at least specific kinds of students, as a threat to education, to free speech, to civilization, even to life itself. In speaking against students, these speech acts also speak for more or less explicitly articulated sets of values: freedom, reason, education, democracy. Students are failing to reproduce the required norms of conduct. Even if that failure is explained as a result of ideological shifts that students are not held responsible for – whether it be neoliberalism, managerialism or a new sexual puritanism – it is in the bodies of students that the failure is located. Students are not transmitting the right message, or are evidence that we have failed to transmit the right message. Students have become an error message, a beep, beep, that is announcing system failure.

In describing the problem of how students have become the problem, I analyze some recent writings that seem to be concerned with distinct issues even if they all address the demise of higher education and involve a kind of nostalgia for something that has been, or is being, lost. I have made the decision to quote from these texts without citing the authors by name. I wish to treat each text as an instance in a wider intertextual web and thus to depersonalise the material. Some of these texts do cite each other, and by evoking the figure of the problem student (who travels through this terrain with an accumulating pace and velocity) they all participate in the making of a shared world.

The “problem student” is a constellation of related figures: the consuming student, the censoring student, the over-sensitive student, and the complaining student. By considering how these figures are related we can explore connections that are being made through them, connections between, for example, neoliberalism in higher education, a concern with safe spaces, and the struggle against sexual harassment. These connections are being made without being explicitly articulated. We need to make these connections explicit in order to challenge them. This is what “against students” is really about.

One of my concerns in Willful Subjects was with the politics of dismissal. I was interested in how various points of view can be dismissed by being swept away or swept up by the charge of willfulness. So: What protesters are protesting about can be ignored when protesters are assumed to be suffering from too much will; they are assumed to be opposing something because they are being oppositional. The figures of the consuming student, censoring student, over-sensitive student, and complaining student are also doing something, they are up to something. These figures circulate in order to sweep something up. Different student protests can be dismissed as products of weaknesses of moral character (generated by “student culture” or “campus politics”) and as the cause of a more general decline in values and standards.

Let’s begin with critiques of neoliberalism and higher education. These are critiques I would share. I too would be critical of how universities are managed as businesses; I too would be critical of the transformation of education into a commodity; of how students are treated as consumers. I too am aware of the burdens of bureaucracy and how we can end up pushing paper around just to leave a trail.

Critiques of neoliberalism can also involve a vigorous sweeping: Whatever is placed near the object of critique becomes the object of critique. For example, my empirical research into the university’s new equality regime taught me how equality can be dismissed as a symptom of neo-liberalism, as “just another” mechanism for ensuring academic compliance. UK Home Secretary and Minister for Women and Equality Theresa May justified a withdrawal from some of the stated commitments in the 2010 Equality Act by arguing the law “would have been just another bureaucratic box to be ticked. It would have meant more time filling in forms and less time focusing on policies that will make a real difference to people’s life chances.” The practitioners I researched in On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life talked of how academics use similar arguments: that these forms and procedures are just another “box to be ticked,” in order to dismiss the more general relevance of equality to their work (“a real difference”). They can then enact non-compliance with equality as a form of resistance to bureaucracy. Equality becomes something imposed by management, as what would, if taken seriously, constrain life and labor. Whilst we might want to critique how equality is bureaucratized, we need to challenge how that very critique can be used to dismiss equality.

What do I mean by “against students”? By using this expression I am trying to describe a series of speech acts which consistently position students, or at least specific kinds of students, as a threat to education, to free speech, to civilization, even to life itself. In speaking against students, these speech acts also speak for more or less explicitly articulated sets of values: freedom, reason, education, democracy. Students are failing to reproduce the required norms of conduct. Even if that failure is explained as a result of ideological shifts that students are not held responsible for – whether it be neoliberalism, managerialism or a new sexual puritanism – it is in the bodies of students that the failure is located. Students are not transmitting the right message, or are evidence that we have failed to transmit the right message. Students have become an error message, a beep, beep, that is announcing system failure.

In describing the problem of how students have become the problem, I analyze some recent writings that seem to be concerned with distinct issues even if they all address the demise of higher education and involve a kind of nostalgia for something that has been, or is being, lost. I have made the decision to quote from these texts without citing the authors by name. I wish to treat each text as an instance in a wider intertextual web and thus to depersonalise the material. Some of these texts do cite each other, and by evoking the figure of the problem student (who travels through this terrain with an accumulating pace and velocity) they all participate in the making of a shared world.

The “problem student” is a constellation of related figures: the consuming student, the censoring student, the over-sensitive student, and the complaining student. By considering how these figures are related we can explore connections that are being made through them, connections between, for example, neoliberalism in higher education, a concern with safe spaces, and the struggle against sexual harassment. These connections are being made without being explicitly articulated. We need to make these connections explicit in order to challenge them. This is what “against students” is really about.

One of my concerns in Willful Subjects was with the politics of dismissal. I was interested in how various points of view can be dismissed by being swept away or swept up by the charge of willfulness. So: What protesters are protesting about can be ignored when protesters are assumed to be suffering from too much will; they are assumed to be opposing something because they are being oppositional. The figures of the consuming student, censoring student, over-sensitive student, and complaining student are also doing something, they are up to something. These figures circulate in order to sweep something up. Different student protests can be dismissed as products of weaknesses of moral character (generated by “student culture” or “campus politics”) and as the cause of a more general decline in values and standards.

Let’s begin with critiques of neoliberalism and higher education. These are critiques I would share. I too would be critical of how universities are managed as businesses; I too would be critical of the transformation of education into a commodity; of how students are treated as consumers. I too am aware of the burdens of bureaucracy and how we can end up pushing paper around just to leave a trail.

Critiques of neoliberalism can also involve a vigorous sweeping: Whatever is placed near the object of critique becomes the object of critique. For example, my empirical research into the university’s new equality regime taught me how equality can be dismissed as a symptom of neo-liberalism, as “just another” mechanism for ensuring academic compliance. UK Home Secretary and Minister for Women and Equality Theresa May justified a withdrawal from some of the stated commitments in the 2010 Equality Act by arguing the law “would have been just another bureaucratic box to be ticked. It would have meant more time filling in forms and less time focusing on policies that will make a real difference to people’s life chances.” The practitioners I researched in On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life talked of how academics use similar arguments: that these forms and procedures are just another “box to be ticked,” in order to dismiss the more general relevance of equality to their work (“a real difference”). They can then enact non-compliance with equality as a form of resistance to bureaucracy. Equality becomes something imposed by management, as what would, if taken seriously, constrain life and labor. Whilst we might want to critique how equality is bureaucratized, we need to challenge how that very critique can be used to dismiss equality.

What do I mean by “against students”? By using this expression I am trying to describe a series of speech acts which consistently position students, or at least specific kinds of students, as a threat to education, to free speech, to civilization, even to life itself. In speaking against students, these speech acts also speak for more or less explicitly articulated sets of values: freedom, reason, education, democracy. Students are failing to reproduce the required norms of conduct. Even if that failure is explained as a result of ideological shifts that students are not held responsible for – whether it be neoliberalism, managerialism or a new sexual puritanism – it is in the bodies of students that the failure is located. Students are not transmitting the right message, or are evidence that we have failed to transmit the right message. Students have become an error message, a beep, beep, that is announcing system failure.

In describing the problem of how students have become the problem, I analyze some recent writings that seem to be concerned with distinct issues even if they all address the demise of higher education and involve a kind of nostalgia for something that has been, or is being, lost. I have made the decision to quote from these texts without citing the authors by name. I wish to treat each text as an instance in a wider intertextual web and thus to depersonalise the material. Some of these texts do cite each other, and by evoking the figure of the problem student (who travels through this terrain with an accumulating pace and velocity) they all participate in the making of a shared world.

The “problem student” is a constellation of related figures: the consuming student, the censoring student, the over-sensitive student, and the complaining student. By considering how these figures are related we can explore connections that are being made through them, connections between, for example, neoliberalism in higher education, a concern with safe spaces, and the struggle against sexual harassment. These connections are being made without being explicitly articulated. We need to make these connections explicit in order to challenge them. This is what “against students” is really about.

One of my concerns in Willful Subjects was with the politics of dismissal. I was interested in how various points of view can be dismissed by being swept away or swept up by the charge of willfulness. So: What protesters are protesting about can be ignored when protesters are assumed to be suffering from too much will; they are assumed to be opposing something because they are being oppositional. The figures of the consuming student, censoring student, over-sensitive student, and complaining student are also doing something, they are up to something. These figures circulate in order to sweep something up. Different student protests can be dismissed as products of weaknesses of moral character (generated by “student culture” or “campus politics”) and as the cause of a more general decline in values and standards.

Let’s begin with critiques of neoliberalism and higher education. These are critiques I would share. I too would be critical of how universities are managed as businesses; I too would be critical of the transformation of education into a commodity; of how students are treated as consumers. I too am aware of the burdens of bureaucracy and how we can end up pushing paper around just to leave a trail.

Critiques of neoliberalism can also involve a vigorous sweeping: Whatever is placed near the object of critique becomes the object of critique. For example, my empirical research into the university’s new equality regime taught me how equality can be dismissed as a symptom of neo-liberalism, as “just another” mechanism for ensuring academic compliance. UK Home Secretary and Minister for Women and Equality Theresa May justified a withdrawal from some of the stated commitments in the 2010 Equality Act by arguing the law “would have been just another bureaucratic box to be ticked. It would have meant more time filling in forms and less time focusing on policies that will make a real difference to people’s life chances.” The practitioners I researched in On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life talked of how academics use similar arguments: that these forms and procedures are just another “box to be ticked,” in order to dismiss the more general relevance of equality to their work (“a real difference”). They can then enact non-compliance with equality as a form of resistance to bureaucracy. Equality becomes something imposed by management, as what would, if taken seriously, constrain life and labor. Whilst we might want to critique how equality is bureaucratized, we need to challenge how that very critique can be used to dismiss equality.

I remember being nervous when I flew into Atyrau, Kazakhstan. Before boarding the flight, one of the business managers who organized the trip sent me a message with precise instructions on how to navigate the local airport:

Once you land, get into the bus on the right side of the driver. This side opens to the terminal. Pass through immigration, pick up your luggage, and go through Customs. The flight crew will pass out white migration cards. Fill them out, and keep it with your passport. You will need to carry these documents on you at all times once you’ve landed.

Another coworker, who had flown in the night before, warned us not to worry if we found ourselves in jail. Don’t panic if you find yourself in jail. Give me a call and we’ll bail you out. Maybe she was joking.

The flight itself was uncanny. I was flying in from Frankfurt, but it felt a lot like a local American flight to somewhere in the Midwest. The plane was filled with middle-aged American businessmen equipped with black Lenovo laptops and baseball caps. The man next to me wore a cowboy-esque leather jacket over a blue-collared business shirt.

After I landed in Atyrau’s single-gate airport, I located my driver, who was holding a card with my name on it. He swiftly led me into a seven-seater Mercedes van and drove me to my hotel, one of the only hotels in the city. Everyone from the flight also seemed to stay there. The drive was short. The city was overwhelmingly gray. Most of it was visibly poor. The hotel was an oasis of wealth.

Across from the hotel was another one of these oases: a gated community with beige bungalows. This was presumably where the expats who worked for Chevron lived. There was a Burger King and a KFC within walking distance. Everyone spoke a bit of English.

Security was taken extremely seriously. Each time we entered one of Chevron’s offices, our passports were checked, our bags were inspected, and our bodies were patted down. Video cameras were mounted on the ceilings of the hallways and conference rooms. We were instructed to travel only using Chevron’s fleet of taxis, which were wired up with cameras and mics.

All of this — Atyrau’s extreme security measures and the steady flow of American businesspeople — comes from the fact that the city is home to Kazakhstan’s biggest and most important oil extraction project. In 1993, shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union, the newly independent nation opened its borders to foreign investment. Kazakhstan’s state-owned energy company agreed to partner with Chevron in a joint venture to extract oil.

The project was named Tengizchevroil, or TCO for short, and it was granted an exclusive forty-year right to the Tengiz oil field near Atyrau. Tengiz carries roughly 26 billion barrels of oil, making it one of the largest fields in the world. Chevron has poured money into the joint venture with the goal of using new technology to increase oil production at the site. And I, a Microsoft engineer, was sent there to help.

Despite the climate crisis that our planet faces, Big Oil is doubling down on fossil fuels. At over 30 billion barrels of crude oil a year, production has never been higher. Now, with the help of tech companies like Microsoft, oil companies are using cutting-edge technology to produce even more.

The collaboration between Big Tech and Big Oil might seem counterintuitive. Culturally, who could be further apart? Moreover, many tech companies portray themselves as leaders in corporate sustainability. They try to out-do each other in their support for green initiatives. But in reality, Big Tech and Big Oil are closely linked, and only getting closer.

The foundation of their partnership is the cloud. Cloud computing, like many of today’s online subscription services, is a way for companies to rent servers, as opposed to purchasing them. (This model is more specifically called the public cloud.) It’s like choosing to rent a movie on iTunes for $2.99 instead of buying the DVD for $14.99. In the old days, a company would have to run its website from a server that it bought and maintained itself. By using the cloud, that same company can outsource its infrastructure needs to a cloud provider.

The market is dominated by Amazon’s cloud computing wing, Amazon Web Services (AWS), which now makes up more than half of all of Amazon’s operating income. AWS has grown fast: in 2014, its revenue was $4.6 billion; in 2019, it is set to surpass $36 billion. So many companies run on AWS that when one of its most popular services went down briefly in 2017, it felt like the entire internet stopped working.

I remember being nervous when I flew into Atyrau, Kazakhstan. Before boarding the flight, one of the business managers who organized the trip sent me a message with precise instructions on how to navigate the local airport:

Once you land, get into the bus on the right side of the driver. This side opens to the terminal. Pass through immigration, pick up your luggage, and go through Customs. The flight crew will pass out white migration cards. Fill them out, and keep it with your passport. You will need to carry these documents on you at all times once you’ve landed.

Another coworker, who had flown in the night before, warned us not to worry if we found ourselves in jail. Don’t panic if you find yourself in jail. Give me a call and we’ll bail you out. Maybe she was joking.

The flight itself was uncanny. I was flying in from Frankfurt, but it felt a lot like a local American flight to somewhere in the Midwest. The plane was filled with middle-aged American businessmen equipped with black Lenovo laptops and baseball caps. The man next to me wore a cowboy-esque leather jacket over a blue-collared business shirt.

After I landed in Atyrau’s single-gate airport, I located my driver, who was holding a card with my name on it. He swiftly led me into a seven-seater Mercedes van and drove me to my hotel, one of the only hotels in the city. Everyone from the flight also seemed to stay there. The drive was short. The city was overwhelmingly gray. Most of it was visibly poor. The hotel was an oasis of wealth.

Across from the hotel was another one of these oases: a gated community with beige bungalows. This was presumably where the expats who worked for Chevron lived. There was a Burger King and a KFC within walking distance. Everyone spoke a bit of English.

Security was taken extremely seriously. Each time we entered one of Chevron’s offices, our passports were checked, our bags were inspected, and our bodies were patted down. Video cameras were mounted on the ceilings of the hallways and conference rooms. We were instructed to travel only using Chevron’s fleet of taxis, which were wired up with cameras and mics.

All of this — Atyrau’s extreme security measures and the steady flow of American businesspeople — comes from the fact that the city is home to Kazakhstan’s biggest and most important oil extraction project. In 1993, shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union, the newly independent nation opened its borders to foreign investment. Kazakhstan’s state-owned energy company agreed to partner with Chevron in a joint venture to extract oil.

The project was named Tengizchevroil, or TCO for short, and it was granted an exclusive forty-year right to the Tengiz oil field near Atyrau. Tengiz carries roughly 26 billion barrels of oil, making it one of the largest fields in the world. Chevron has poured money into the joint venture with the goal of using new technology to increase oil production at the site. And I, a Microsoft engineer, was sent there to help.

Despite the climate crisis that our planet faces, Big Oil is doubling down on fossil fuels. At over 30 billion barrels of crude oil a year, production has never been higher. Now, with the help of tech companies like Microsoft, oil companies are using cutting-edge technology to produce even more.

The collaboration between Big Tech and Big Oil might seem counterintuitive. Culturally, who could be further apart? Moreover, many tech companies portray themselves as leaders in corporate sustainability. They try to out-do each other in their support for green initiatives. But in reality, Big Tech and Big Oil are closely linked, and only getting closer.

The foundation of their partnership is the cloud. Cloud computing, like many of today’s online subscription services, is a way for companies to rent servers, as opposed to purchasing them. (This model is more specifically called the public cloud.) It’s like choosing to rent a movie on iTunes for $2.99 instead of buying the DVD for $14.99. In the old days, a company would have to run its website from a server that it bought and maintained itself. By using the cloud, that same company can outsource its infrastructure needs to a cloud provider.

The market is dominated by Amazon’s cloud computing wing, Amazon Web Services (AWS), which now makes up more than half of all of Amazon’s operating income. AWS has grown fast: in 2014, its revenue was $4.6 billion; in 2019, it is set to surpass $36 billion. So many companies run on AWS that when one of its most popular services went down briefly in 2017, it felt like the entire internet stopped working.

I remember being nervous when I flew into Atyrau, Kazakhstan. Before boarding the flight, one of the business managers who organized the trip sent me a message with precise instructions on how to navigate the local airport:

Once you land, get into the bus on the right side of the driver. This side opens to the terminal. Pass through immigration, pick up your luggage, and go through Customs. The flight crew will pass out white migration cards. Fill them out, and keep it with your passport. You will need to carry these documents on you at all times once you’ve landed.

Another coworker, who had flown in the night before, warned us not to worry if we found ourselves in jail. Don’t panic if you find yourself in jail. Give me a call and we’ll bail you out. Maybe she was joking.

The flight itself was uncanny. I was flying in from Frankfurt, but it felt a lot like a local American flight to somewhere in the Midwest. The plane was filled with middle-aged American businessmen equipped with black Lenovo laptops and baseball caps. The man next to me wore a cowboy-esque leather jacket over a blue-collared business shirt.

After I landed in Atyrau’s single-gate airport, I located my driver, who was holding a card with my name on it. He swiftly led me into a seven-seater Mercedes van and drove me to my hotel, one of the only hotels in the city. Everyone from the flight also seemed to stay there. The drive was short. The city was overwhelmingly gray. Most of it was visibly poor. The hotel was an oasis of wealth.

Across from the hotel was another one of these oases: a gated community with beige bungalows. This was presumably where the expats who worked for Chevron lived. There was a Burger King and a KFC within walking distance. Everyone spoke a bit of English.

Security was taken extremely seriously. Each time we entered one of Chevron’s offices, our passports were checked, our bags were inspected, and our bodies were patted down. Video cameras were mounted on the ceilings of the hallways and conference rooms. We were instructed to travel only using Chevron’s fleet of taxis, which were wired up with cameras and mics.

All of this — Atyrau’s extreme security measures and the steady flow of American businesspeople — comes from the fact that the city is home to Kazakhstan’s biggest and most important oil extraction project. In 1993, shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union, the newly independent nation opened its borders to foreign investment. Kazakhstan’s state-owned energy company agreed to partner with Chevron in a joint venture to extract oil.

The project was named Tengizchevroil, or TCO for short, and it was granted an exclusive forty-year right to the Tengiz oil field near Atyrau. Tengiz carries roughly 26 billion barrels of oil, making it one of the largest fields in the world. Chevron has poured money into the joint venture with the goal of using new technology to increase oil production at the site. And I, a Microsoft engineer, was sent there to help.

Despite the climate crisis that our planet faces, Big Oil is doubling down on fossil fuels. At over 30 billion barrels of crude oil a year, production has never been higher. Now, with the help of tech companies like Microsoft, oil companies are using cutting-edge technology to produce even more.

The collaboration between Big Tech and Big Oil might seem counterintuitive. Culturally, who could be further apart? Moreover, many tech companies portray themselves as leaders in corporate sustainability. They try to out-do each other in their support for green initiatives. But in reality, Big Tech and Big Oil are closely linked, and only getting closer.

The foundation of their partnership is the cloud. Cloud computing, like many of today’s online subscription services, is a way for companies to rent servers, as opposed to purchasing them. (This model is more specifically called the public cloud.) It’s like choosing to rent a movie on iTunes for $2.99 instead of buying the DVD for $14.99. In the old days, a company would have to run its website from a server that it bought and maintained itself. By using the cloud, that same company can outsource its infrastructure needs to a cloud provider.

The market is dominated by Amazon’s cloud computing wing, Amazon Web Services (AWS), which now makes up more than half of all of Amazon’s operating income. AWS has grown fast: in 2014, its revenue was $4.6 billion; in 2019, it is set to surpass $36 billion. So many companies run on AWS that when one of its most popular services went down briefly in 2017, it felt like the entire internet stopped working.

I remember being nervous when I flew into Atyrau, Kazakhstan. Before boarding the flight, one of the business managers who organized the trip sent me a message with precise instructions on how to navigate the local airport:

Once you land, get into the bus on the right side of the driver. This side opens to the terminal. Pass through immigration, pick up your luggage, and go through Customs. The flight crew will pass out white migration cards. Fill them out, and keep it with your passport. You will need to carry these documents on you at all times once you’ve landed.

Another coworker, who had flown in the night before, warned us not to worry if we found ourselves in jail. Don’t panic if you find yourself in jail. Give me a call and we’ll bail you out. Maybe she was joking.

The flight itself was uncanny. I was flying in from Frankfurt, but it felt a lot like a local American flight to somewhere in the Midwest. The plane was filled with middle-aged American businessmen equipped with black Lenovo laptops and baseball caps. The man next to me wore a cowboy-esque leather jacket over a blue-collared business shirt.

After I landed in Atyrau’s single-gate airport, I located my driver, who was holding a card with my name on it. He swiftly led me into a seven-seater Mercedes van and drove me to my hotel, one of the only hotels in the city. Everyone from the flight also seemed to stay there. The drive was short. The city was overwhelmingly gray. Most of it was visibly poor. The hotel was an oasis of wealth.

Across from the hotel was another one of these oases: a gated community with beige bungalows. This was presumably where the expats who worked for Chevron lived. There was a Burger King and a KFC within walking distance. Everyone spoke a bit of English.

Security was taken extremely seriously. Each time we entered one of Chevron’s offices, our passports were checked, our bags were inspected, and our bodies were patted down. Video cameras were mounted on the ceilings of the hallways and conference rooms. We were instructed to travel only using Chevron’s fleet of taxis, which were wired up with cameras and mics.

All of this — Atyrau’s extreme security measures and the steady flow of American businesspeople — comes from the fact that the city is home to Kazakhstan’s biggest and most important oil extraction project. In 1993, shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union, the newly independent nation opened its borders to foreign investment. Kazakhstan’s state-owned energy company agreed to partner with Chevron in a joint venture to extract oil.

The project was named Tengizchevroil, or TCO for short, and it was granted an exclusive forty-year right to the Tengiz oil field near Atyrau. Tengiz carries roughly 26 billion barrels of oil, making it one of the largest fields in the world. Chevron has poured money into the joint venture with the goal of using new technology to increase oil production at the site. And I, a Microsoft engineer, was sent there to help.

Despite the climate crisis that our planet faces, Big Oil is doubling down on fossil fuels. At over 30 billion barrels of crude oil a year, production has never been higher. Now, with the help of tech companies like Microsoft, oil companies are using cutting-edge technology to produce even more.

The collaboration between Big Tech and Big Oil might seem counterintuitive. Culturally, who could be further apart? Moreover, many tech companies portray themselves as leaders in corporate sustainability. They try to out-do each other in their support for green initiatives. But in reality, Big Tech and Big Oil are closely linked, and only getting closer.

The foundation of their partnership is the cloud. Cloud computing, like many of today’s online subscription services, is a way for companies to rent servers, as opposed to purchasing them. (This model is more specifically called the public cloud.) It’s like choosing to rent a movie on iTunes for $2.99 instead of buying the DVD for $14.99. In the old days, a company would have to run its website from a server that it bought and maintained itself. By using the cloud, that same company can outsource its infrastructure needs to a cloud provider.

The market is dominated by Amazon’s cloud computing wing, Amazon Web Services (AWS), which now makes up more than half of all of Amazon’s operating income. AWS has grown fast: in 2014, its revenue was $4.6 billion; in 2019, it is set to surpass $36 billion. So many companies run on AWS that when one of its most popular services went down briefly in 2017, it felt like the entire internet stopped working.

I remember being nervous when I flew into Atyrau, Kazakhstan. Before boarding the flight, one of the business managers who organized the trip sent me a message with precise instructions on how to navigate the local airport:

Once you land, get into the bus on the right side of the driver. This side opens to the terminal. Pass through immigration, pick up your luggage, and go through Customs. The flight crew will pass out white migration cards. Fill them out, and keep it with your passport. You will need to carry these documents on you at all times once you’ve landed.

Another coworker, who had flown in the night before, warned us not to worry if we found ourselves in jail. Don’t panic if you find yourself in jail. Give me a call and we’ll bail you out. Maybe she was joking.

The flight itself was uncanny. I was flying in from Frankfurt, but it felt a lot like a local American flight to somewhere in the Midwest. The plane was filled with middle-aged American businessmen equipped with black Lenovo laptops and baseball caps. The man next to me wore a cowboy-esque leather jacket over a blue-collared business shirt.

After I landed in Atyrau’s single-gate airport, I located my driver, who was holding a card with my name on it. He swiftly led me into a seven-seater Mercedes van and drove me to my hotel, one of the only hotels in the city. Everyone from the flight also seemed to stay there. The drive was short. The city was overwhelmingly gray. Most of it was visibly poor. The hotel was an oasis of wealth.

Across from the hotel was another one of these oases: a gated community with beige bungalows. This was presumably where the expats who worked for Chevron lived. There was a Burger King and a KFC within walking distance. Everyone spoke a bit of English.

Security was taken extremely seriously. Each time we entered one of Chevron’s offices, our passports were checked, our bags were inspected, and our bodies were patted down. Video cameras were mounted on the ceilings of the hallways and conference rooms. We were instructed to travel only using Chevron’s fleet of taxis, which were wired up with cameras and mics.